"Hurt Feelings" and Other Lies

thoughts regarding the recent stabbing of Salman Rushdie

I imagine he thought he had put it all behind him. Over thirty years after the fatwa calling for his head, Salman Rushdie could be seen dating glamorous women, attending celebrity parties and HBO premieres—generally enjoying the life of a celebrated writer.

Clearly, he felt safe. And maybe he was—many millions of Muslims mean him no harm. But that still left countless others who felt he had committed an unforgivable crime, one that meant he no longer retained the right to life.

It was that illusion of safety that allowed him to go on stage in front of thousands of people without asking anything of attendees other than a ticket and an ID check.

His attacker was 24, born a decade after the Satanic Verses was published. He never lived through the drama that unfolded in the years following the publication, never heard the call of the fatwa as it was proclaimed. But fanaticism has a long memory, one that can stay alive in the community even as it is forgotten by broader society, passed down from believer to believer.

It was a mistake to presume that something had changed just because the religion of peace no longer makes regular headlines, or because Rushdie appeared to be “getting away with it” and living an open life.

The ayatollah who passed the death sentence on Rushdie himself died only months after the declaration. But over 30 years later, his fatwa lives on.

We are making a mistake too. We are presuming that “hurt feelings” have anything to do with it.

On July 12, 2005, a young man named Mohammed Bouyeri was standing trial in the Netherlands. He was charged with the murder of one man, the attempted murder of several others, and of terrorizing the Dutch population. The man he killed was named Theo van Gogh, great grandnephew of the master artist, who was now working as a filmmaker. He worked with his friend, ex-Muslim Ayaan Hirsi Ali, to create a film provocatively titled “Submission”. Muslims declared it blasphemy.

For this crime, Mohammed Bouyeri shot and stabbed Theo as he cycled into work, then used knives to pin notes onto Theo’s corpse. One of the notes was a threat against Hirsi Ali, who then went into hiding.

It is hard to imagine a level of religious anguish so deep that it moves one to slice the throat of another. Were the islamists who decapitated “infidels” in Syria just deeply hurt—sensitive souls tormented by devastating words?

In his trial, Bouyeri made his motivations clear.

“So the story that I felt insulted as a Moroccan, or because he called me a goat fucker, that is all nonsense. I acted out of faith. And I made it clear that if it had been my own father, or my little brother, I would have done the same thing”.

He said he felt obligated to “cut off the heads of all those who insult Allah and his prophet”.

It was not an act borne from offense—or at least, nothing like offense as we know it. It was not a crime of passion. He killed matter-of-factly, performing his duty as a follower of god.

When the faithful speak about “hurt feelings”, they are borrowing the terminology they believe would sound most sympathetic to Western ears, not unlike when the Chinese Communist Party charges the United States of “marginalization” or insufficient “inclusivity”. The hurt feelings are professed almost exclusively to Westerners, less so amongst themselves—where the focus is far more on matters of material importance.

The maneuver is easiest to spot on the international stage.

Savvy politicians like Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Imran Khan have used Western conceptions of “hate speech” to appeal for a global blasphemy law. Khan—who spent his formative years in upper-class circles in England, even marrying a friend of the late Princess Diana—understands intimately what the Western ear wants to hear.

"We Muslim leaders have not explained to the Western societies how painful it is when our Prophet is maligned, mocked, ridiculed," said the former PM in a UN side event on hate speech, co-hosted by authoritarian zealot Recep Tayyip Erdogan. "Why does it cause so much pain? Because the Prophet lives in our hearts. And we all know that the pain of the heart is far, far, far greater than physical pain.”

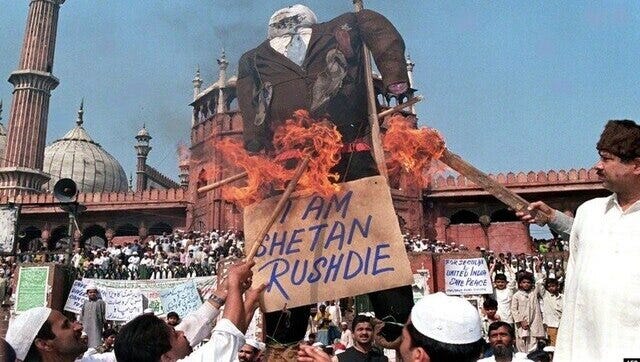

Burning books, violent protests that kill and wound countless, vigilante attacks slaughtering humans as if they were sheep… are those the behaviors of people with a serious case of an achy-breaky-heart?

Far be it for me to disbelieve such moving testimony by a politician in one of the most corrupt countries on the planet, but from here, the behavior of Muslims when confronted with blasphemy looks remarkably like rage.

But rage doesn’t sell well in the West. Rage sounds like abuse, and abusers get no love here.

In other societies one might get acquiescence by flexing muscles—by the assertion of dominance and power. But in the West, a different tact has to be taken. Here, moral progress has reached a point where the people recognize the sins of the past, and so the powerful attempt to regain moral authority through performative genuflections to the “marginalized”. In the West, power rests behind the facade of victimhood.

And in a society where material needs rarely make the difference between life and death, grievances take on a psychic nature. Injustice here is as likely to be defined as a crime against the inner sense of self as one against the outer body.

Once you understand these terms, it is a simple thing to reframe the discussion in your favor.

Believers who wish to see state-sponsored force enacted against blasphemers can point to the harm it causes to their social standing and, therefore, inner state. In this way, they are no longer extreme dogmatists depriving others of their freedom of speech, they are victims of hate speech by islamophobes.

Amazingly, it is working.

Western countries and international bodies are quietly but meaningfully moving in the direction of more speech restrictions based on the loose and subjective criteria of “hate” (alongside other loosely-defined criteria such as “public order”), with social media companies following suit—what some are calling a global free speech recession.

The blasphemy law proponents are happy to see things turning in their favor.

When the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted the resolution introduced by Pakistan declaring March 22 to be the “International Day to Combat Islamophobia”, Imran Khan applauded. Khan, whose time as Prime Minister saw an alarming rise in mob violence and lynchings of religious minorities, saw a path to victory: “Today UN has finally recognised the grave challenge confronting the world: of Islamophobia, respect for religious symbols & practices & of curtailing systematic hate speech & discrimination against Muslims. Next challenge is to ensure implementation of this landmark resolution.”

Khan isn’t alone in conflating discrimination against Muslims with respect for Muslim ideas. There is no major Muslim organization that allows for a distinction between acts of discrimination against Muslims and the badmouthing of their faith. And this makes sense—in the eyes of believers, both are religiously illegal acts (and if anything, the crime against god is the more egregious offense).

Recognizing that the secular West does not acknowledge crimes against god, however, they point instead to hurt feelings (a grievous wound that nevertheless appears to vanish when one encounters materials not intended for Western audiences).

The politicians and civil leaders might be speaking strategically, but one can get honesty from the fundamentalists. They are clear, time and time again, that they believe the words themselves to be a crime—that it matters not how it makes anyone “feel”. But their words are never taken at face value, and are instead explained away by the more moderate (read: nonviolent) believers, who reassure us that all will be well once there is enough acceptance of Muslims and respect towards Islam.

With one promising violence, and the other manipulating the liberal language of care and harm, the two form a perfectly balanced weapon. The explicit threat of violence, and the implicit threat of social stigma come together to frighten and bamboozle Westerners, who have already been sensitized by an ideology that expertly re-packages the illiberality of old into an irresistible form.

This ideology, referred to commonly as wokeism, is not in itself very dangerous—and on a superficial level it even appears good, a logical extension of social progress. It is wrong, in that sense, to compare the threats against Rushdie to the threats made against gender-critical author J.K. Rowling. They are not similar in many meaningful ways—not in their substantiality nor in their scope. But while they cannot be easily compared, they are, however, related. The ideology that produces death threats against Rowling is the same that is acting as a solvent on the liberal roots of our society, paralyzing defenses against the greater authoritarianisms.

Sean O’Grady, associate editor of the Independent, exemplified the confusion and cowardice perfectly in his review of a documentary about the Satanic Verses controversy.

“Rushdie’s silly, childish book should be banned under today’s anti-hate legislation. It’s no better than racist graffiti on a bus stop. I wouldn’t have it in my house, out of respect to Muslim people and contempt for Rushdie, and because it sounds quite boring. I’d be quite inclined to burn it, in fact. It’s a free country, after all.”

What is really scary is the UK's The Independent saying things that are little different from the

fatwa placed on Rushdie! What is all this nonsense about not hurting the feelings of patriarchal authoritarian theocracies that murder women, gays and apostates freely, just as part of their usual day? What are these apologists for atrocities thinking and what motivates them? We need to acknowledge that there are certain belief systems, societies and countries who despise all other societies or individuals and will without hesitation decapitate them without a second thought. These systems and societies are outside of the civilized humanistic world, in another hellish

universe that should be shunned and publicly shamed. We should not sit down for talks about

nuclear arms or anything else. They should be ignored and isolated forever.

Religious faith is a form of mental illness, regardless of whether the DSM recognizes it as such. Yes, mental illness can manifest in large groups of humans. Even dominant groups of humans. It has done so throughout history, and this fact is why every human who can should learn defensive arts. You never know what sort of brain fungus the person next to you is infected with.